If you’re not interested in the context, you can skip straight to the good stuff.

I was eager to start using concepts because they allowed me to control templates the way I always wanted to. I immediately switched to modules for new projects because I have hated “include guards” since my early days of learning C++ in the 90s.

#ifndef STUPID_GUARD_H

#define STUPID_GUARD_H

#include <iostream>

void Complain()

{

std::cout << "I don't want to do this anymore.\n";

}

#endif // STUPID_GUARD_HCode language: C++ (cpp)Sure, we can pretty reliably depend on #pragma once these days, but it’s still technically not “portable,” portability being a common problem that is also addressed in the example of the new feature this post is about, that feature being reflection.

When a compiler toolchain became available that allowed me to play with reflection, I already had a use case sitting in my src folder begging for the kind of solution reflection can provide, that use case being reading a struct from a file without hardcoding the size.

“That’s easy!” you exclaim. Sure, on the surface it is. You read a binary file into an array of chars, then cast that array to a pointer of the type of the struct. Done.

Except when it doesn’t work.

Why wouldn’t it work? This approach will sometimes fail because of alignment.

When A Byte Is Not A Byte

In order to satisfy alignment requirements of all members of a struct, padding may be inserted after some of its members.

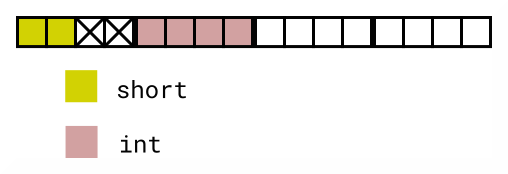

If we look at memory as a series of chunks rather than a stream of bytes it’ll help to illustrate alignment. Let’s visualize our memory as a 16 byte row of 4 byte chunks.

Now let’s place the following struct in it.

struct Example

{

short two_bytes;

int four_bytes;

};Code language: C++ (cpp)On x86 systems, a short is two bytes long and an int is four, so if we use the sizeof operator on our struct, it should report 6, right? Let’s test that theory with the following program.

#include <iostream>

struct Example

{

short two_bytes;

int four_bytes;

};

int main()

{

std::cout << sizeof(Example) << "\n";

return 0;

}Code language: C++ (cpp)If you run this code, you’ll see it prints 8, not 6! This is because the compiler is adding two bytes of padding after the short. Remember our 4 byte chunks of memory? Because the int will take a full chunk, it’s slid over two bytes to line up with the four byte boundary.

This creates a real problem if we’re relying on that sizeof operator to tell us how many bytes to read from the file! Let’s look at a classic real world example1 for context, the BITMAPFILEHEADER that is crucial for reading image data from a .bmp file.

typedef struct tagBITMAPFILEHEADER {

WORD bfType;

DWORD bfSize;

WORD bfReserved1;

WORD bfReserved2;

DWORD bfOffBits;

} BITMAPFILEHEADER, *LPBITMAPFILEHEADER, *PBITMAPFILEHEADER;Code language: C++ (cpp)In the Windows API, a WORD is 2 bytes and a DWORD is 4 bytes. This struct should total 14 bytes, but sizeof reports 16, so if we rely on this we’re going to read past the end of the BITMAPFILEHEADER and into the BITMAPINFOHEADER. We don’t want that!

std::array<char,sizeof(BITMAPFILEHEADER)> fileHeaderData;

std::ifstream file("example.bmp",std::ios::binary);

// FIXME: reads 16 bytes, not 14!

file.read(fileHeaderData.data(),sizeof(BITMAPFILEHEADER));Code language: C++ (cpp)“Okay, but what does this have to do with reflection?” I would be asking if I were reading this up to this point. We have options to handle this situation, but reflection is better than any of them. Let’s compare.

Option #1: Disable Alignment

We can just turn alignment off. You’re allowed to do that, but it has consequences. Alignment is an optimization, so disabling it comes with a performance penalty. But let’s say we don’t care about this. Remember that pesky “portability” mentioned at the outset? There is no standard way to disable alignment outlined in the C++ standard, so our options are compiler specific.

| almost universal | g++/clang++ | MSVC |

|---|---|---|

| | __declspec(align(#)) |

This is not good because we’re likely going to have to litter our code with #ifdefs2 to control which method we use on each platform.

A more modern approach exists; with the C++11 standard came the alignas specifier, so we can manually specify the alignment on each member.

struct Example

{

alignas(2) short two_bytes;

alignas(4) int four_bytes;

};Code language: C++ (cpp)But that comes with its caveats as well. alignas is useful for adding padding, but not useful for removing it.

Option #2: Manually Deserialize Each Member

The next option we have is to leave alignment on and sum the result of the sizeof operator on each member.

static constexpr std::size_t Size()

{

return sizeof(two_bytes)+sizeof(four_bytes);

}Code language: C++ (cpp)This also requires reading each member from the file and populating it individually so we don’t write over the padding. The drawback here is we’ve now added boilerplate code that must be updated each time the structure changes. Every seasoned programmer knows this is a bug waiting to happen.

Option #3: Reflection!

With reflection in C++26, we can obtain information about our struct dynamically at compile time. This allows us to write a Size() function that loops over every data member of the struct and apply the sizeof operator to it.

static constexpr std::size_t Example::Size()

{

std::size_t size=0;

template for (constexpr auto member : std::define_static_array(std::meta::nonstatic_data_members_of(^^Example,std::meta::access_context::unprivileged())))

{

size+=std::meta::size_of(member);

}

return size;

}Code language: C++ (cpp)This isn’t your grandfather’s C++. You might not recognize the following.

-

template for– A new type of loop, specifically an “expansion statement,” that can be used on structural elements like the data members of our struct. -

std::define_static_array– Creates an array that can be iterated over bytemplate forfrom an input range. -

std::meta::nonstatic_data_members_of– This is where we get our input range, a list of data members of our struct. -

^^– The “reflection operator” obtains compile-time metadata that describes a type, in this case ourExamplestruct. -

std::meta::access_context::unprivileged– This tellsstd::meta::nonstatic_data_members_ofto only consider public members of our struct. -

std::meta::size_of– A “reflection metafunction” that obtains the size of a program element represented by a reflection object.

We now have a Size() function that will return the correct size, ignoring padding, even if new public data members are added to the struct later in development! Reflection also helps with our deserialization as well.

std::array<char,Example::Size()> exampleData;

std::ifstream file("example.dat",std::ios::binary);

file.read(exampleData.data(),Example::Size());Code language: C++ (cpp)template for (std::size_t offset=0; constexpr auto member : std::define_static_array(std::meta::nonstatic_data_members_of(^^Example,std::meta::access_context::unprivileged())))

{

std::size_t size=std::meta::size_of(member);

std::memcpy(&this->[:member:],exampleData.data()+offset,size);

offset+=size;

}Code language: C++ (cpp)-

[: ... :]– The “splice” operator reverses reflection. It takes metadata about our program element and pastes it back into the source code.

In the example above, for each data member, in order, we obtain its size from the reflection metadata, paste that member into a std::memcpy call that reads bytes up to the data member’s size, populating the member with those bytes. Then we add the size to an offset that tell us where to start reading the data for the next member in the stream of bytes.

Using reflection, we can generate code at compile time that populates each data member of our struct with bytes from our file stream. This gives us a robust solution that handles the alignment problem and adapts to future changes in the program without needing to be adjusted.

I love this already! It’s a good time to be a C++ programmer!

- A full program demonstrating loading and drawing a bitmap using C++26 and reflection can be found on my GitHub. ↩︎

- The preprocessor is a carryover from C, and removing it from C++ would be a dream come true for many of us. ↩︎

Leave a Reply